Abigail McMann resisted the urge to run. She secured the stack of newspapers under her arm and picked up her pace. Her leather ankle boots rang out a staccato rhythm on the boardwalk, so new she could still smell the cedar. The smell of progress.

Two years ago, red dirt and coyotes ruled where now Abigail hurried past the livery, a barber shop, the seamstress, and the shoemaker. And now Mr. Alcorn was bringing Mr. Cedric Lloyd to Independence.

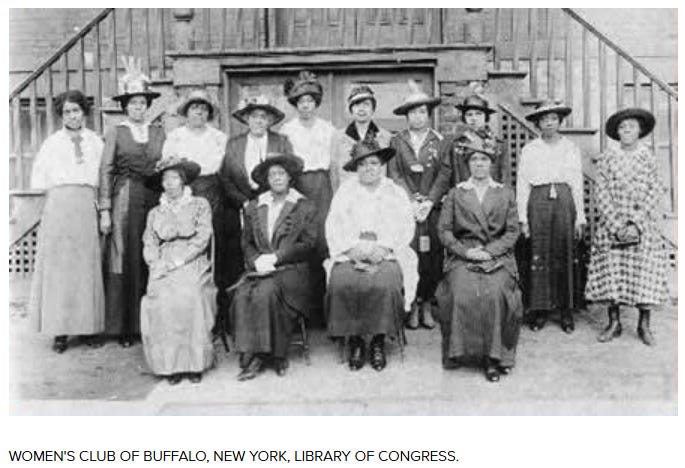

Mr. Lloyd’s visit was a matter of great interest for the ladies of the Independence Ladies Benevolent Society. Several of the ladies were unmarried, after all, and there had been no mention of a Mrs. Lloyd. Mr. Alcorn said that when he observed Mr. Lloyd consulting, in a train station in Louisville, Kentucky, a fourteen-carat gold pocket watch and wearing a custom-fitted twelve-dollar suit and three-dollar leather Oxford shoes, he knew Mr. Lloyd was just the sort of man whose patronage the town of Independence, Oklahoma Territory, sought to encourage. The Independence Ladies Benevolent Society could not agree more.

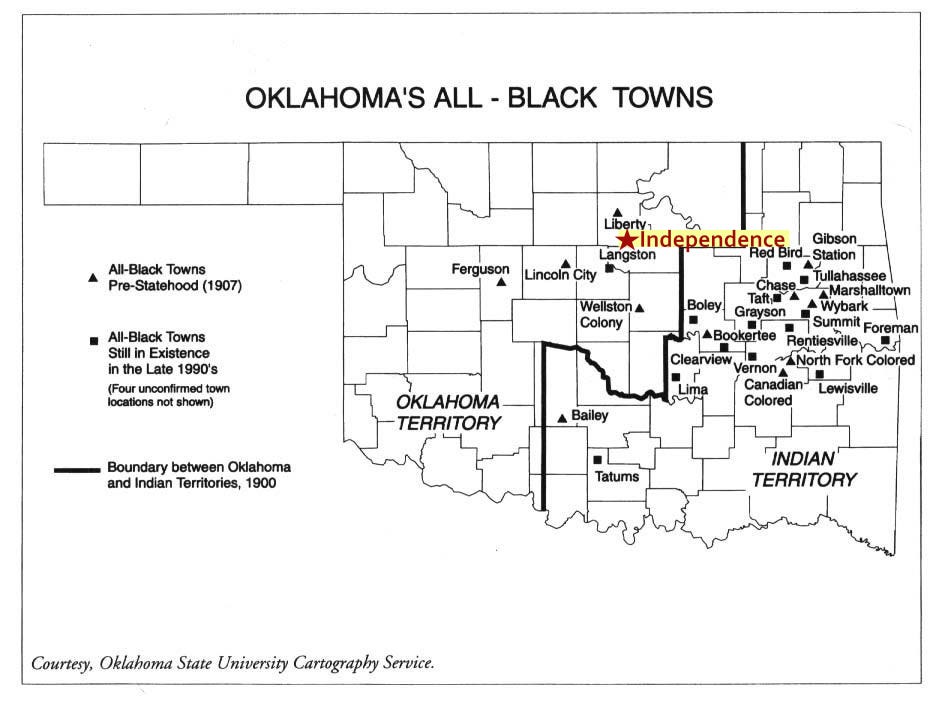

Abigail was unmarried, too, but town sheriff Atlas Reed had shown an interest of late, which she was, late that was. She had been selling newspapers in the crowd of more than three hundred people, many of them Negroes, who gathered in camps and settlements of tents, dugouts, sod houses, and wagons along Independence’s border with Indian Territory. The government would open the Sac and Fox lands on the other side of the border to settlement on September 21, 1891, two weeks hence. Edward McMann built Independence on the border for the very purpose of encouraging Negroes to use it to prepare for the run. Any person over eighteen could claim a parcel of one hundred and sixty acres if he or she could plant the first stake upon it. Dreamers had come from far and wide for an opportunity of free land and freedom. The crowd of hungry homesteaders only grew as the time grew nearer.

Abigail rounded the boardwalk onto Main Street and saw Grady Washington’s horse-drawn buggy riding from the west side of town through the middle of the packed-dirt, crowded Main Street. Four times a week, Grady and his covered coach met the train in Destry, the county capital city sixteen miles to the west. Many Independence newcomers came on the train, and Grady’s coach provided the most comfortable journey for Negroes to get to Independence.

Abigail picked up her pace. The Ladies Benevolent already gathered outside McMann’s Restaurant & Rooming House, just as they had planned, but Elsa Tindall stood at the front.

Elsa’s husband had made the land run of 1889 and claimed a homestead one mile outside of Independence. Unfortunately, Elsa and Isiah had not farmed the claim for one full year before Isiah Tindall fell under his plow and died. Everyone knew “Elsa the Unmarried” was in search of a husband.

Before Abigail could finally reach the rooming house entrance, Elsa stepped down into the street to meet the coach. As Abigail screeched to a halt at the top of the steps, she was left to stare at Elsa’s sharp collar bones and shoulder blades pushing against the threadbare cotton at the back of her shirtwaist.

Grady jumped down from the coach’s driving bench and tied up the horses. “Morning, ladies,” he said with a knowing smile as he pulled open the coach door.

Ever polite, the Ladies Benevolent returned his greeting, but their eyes remained fastened on the coach door as Grady stepped aside.

First emerged Hale Alcorn, a white man of average height in a well-fitting wool suit. A knowing smile similar to Grady's lit blue eyes under thick brows and curved the bushy black mustache above his thin lips. Deep-set eyes focused on each of the ladies as Hale greeted them by name. “Mrs. Tindall, Mrs. Green, Mrs. Washington, Miss Labreau, Miss Hargreaves, Miss McMann. What a marvelous welcome for the newest resident of Independence.”